Trailblazing – Creation of an accessible tour of Fort Brockhurst 2010 (10:15)

Back in 2012, Trail Blazing was an exploration of how creative approaches could make guided tours more accessible to a wider public. Splodge Designs were commissioned to devise a methodology that could be transferable to varied heritage sites, which would be achievable on a low budget and which would broaden the experience of a heritage visit for disabled people.

Splodge Designs worked with Fort Brockhurst. A short film was made about their work and they produced a ‘Guide to Trail Blazing’, which can be downloaded at the end of this page.

The accessible materials and stories produced have been used many times since for Heritage Open Days in Gosport and various outreach visits to local groups.

What an amazing experience! The tactile artwork and sound recordings of days gone by melded perfectly together. Visitor to the Trail Blazing day at Fort Brockhurst, January 2012

Click the picture below to view the short film

Fort Brockhurst

Improved accessibility on a moderate budget.

Below you will find images of the textiles created to tell 6 stories of the fort, along with their description. To listen to an audio description click on the images.

MAGAZINE ROOM – Victorian era (1860s) Cannon firing

The magazine room was used in Victorian times for the storing of the gunpowder for the cannons. In this room one of the cannon rooms has been depicted with three Victorian soldiers.

A Victorian captain shouting his orders at his soldiers for a cannon firing exercise.

A Victorian captain shouting his orders at his soldiers for a cannon firing exercise.

“How many charges have we got?” “10 charges Sergeant.

“We need some more. Go and draw some more from the magazine!”

There is a loud clanking of ammunition charges and also the scraping of loading the charge and cannon ball.

“Remove Tampion…..with round shot load…..FIRE!!!!!!!”

The cannon is then fired with a massive explosion.

The cannons were an essential part of the Forts defences in the Victorian era. Fort Brockhurst and the neighbouring Forts were commissioned by Lord Palmerston, who was Prime Minister at the time. They were built as a deterrent to the possibility of French invasion to Portsmouth, an important Naval Dockyard. Surprisingly many of the cannons are facing away from the sea and dockyard, because Palmerston believed that the French would attempt to capture the Dockyard from the rear.

BARRACK ROOM – Victorian era (1860s) Military and Family life

Barrack rooms were the main living and sleeping quarters of many soldiers from the Victorian Era onwards.

A more recent resident of the barracks from World War Two describes the living conditions of the Victorian soldiers. “Everything would be laid out neatly on the bed on a holdall ready for inspections- his washing kit including his razor, his cleaning kit for his boots, his brasso were all laid out in a set order. Socks had to be folded in the same way, shirts folded neatly. It was everyone’s responsibility to make sure his kit was immaculate, as the army operates on competition, e.g. – this squad has got to be better than that squad and this room has got to be than this room. The Victorian Soldiers’ leisure time was filled with cleaning their own kit. So if you wanted to keep a soldier busy– give him a lot of kit and tell him to get cleaning it! The mattress on which they slept would have been filled with straw.” You may also notice a child’s kangaroo toy on the floor. It belongs to the children who are peeping from behind a curtain. Occasionally some of the Victorian barrack rooms housed the families of some of the Victorian soldiers.

A more recent resident of the barracks from World War Two describes the living conditions of the Victorian soldiers. “Everything would be laid out neatly on the bed on a holdall ready for inspections- his washing kit including his razor, his cleaning kit for his boots, his brasso were all laid out in a set order. Socks had to be folded in the same way, shirts folded neatly. It was everyone’s responsibility to make sure his kit was immaculate, as the army operates on competition, e.g. – this squad has got to be better than that squad and this room has got to be than this room. The Victorian Soldiers’ leisure time was filled with cleaning their own kit. So if you wanted to keep a soldier busy– give him a lot of kit and tell him to get cleaning it! The mattress on which they slept would have been filled with straw.” You may also notice a child’s kangaroo toy on the floor. It belongs to the children who are peeping from behind a curtain. Occasionally some of the Victorian barrack rooms housed the families of some of the Victorian soldiers.

The family was often kept separate from the other male soldiers as they lived behind a large curtain at the back of the room. It was quite common for the wives to perform low paid tasks for soldiers, such as washing cleaning and sewing.

THE BRIDGE World War One The boys march home

A sombre bugle call echoes around the courtyard as there are footsteps of soldiers marching slowly across the wooden bridge.

At the end of World War I Fort Brockhurst was used as a discharge depot for soldiers returning from service abroad. The returning soldiers arrived with all their kit in a kit bag and they were processed in the depot. Each soldier had his own pay book and a list of uniform that he had signed for when he signed on to serve overseas. That was ticked off by the NCOs and they were then issued with a suit and a set of clothes. They were then able to go to the pay office where they handed over their pay book and then received the amount of pay that was owing to them along with a railway ticket to their home. The canaries chirp from within their cages, the reason why the soldiers are carrying canaries in cages was because they were used during the First World War in the trenches to detect gas. The allies realised that canaries had already been used in the mines for detecting gas, so they shipped many canaries across to the trenches to be used as an early warning for gas attacks. One soldier was allocated a canary to look after as they had to be fed and watered. At the end of the war, the canaries were no longer used so the soldier who had looked after them actually bought them back in cages and when they were discharged from the army they were even taken home and became pets.

At the end of World War I Fort Brockhurst was used as a discharge depot for soldiers returning from service abroad. The returning soldiers arrived with all their kit in a kit bag and they were processed in the depot. Each soldier had his own pay book and a list of uniform that he had signed for when he signed on to serve overseas. That was ticked off by the NCOs and they were then issued with a suit and a set of clothes. They were then able to go to the pay office where they handed over their pay book and then received the amount of pay that was owing to them along with a railway ticket to their home. The canaries chirp from within their cages, the reason why the soldiers are carrying canaries in cages was because they were used during the First World War in the trenches to detect gas. The allies realised that canaries had already been used in the mines for detecting gas, so they shipped many canaries across to the trenches to be used as an early warning for gas attacks. One soldier was allocated a canary to look after as they had to be fed and watered. At the end of the war, the canaries were no longer used so the soldier who had looked after them actually bought them back in cages and when they were discharged from the army they were even taken home and became pets.

STABLES World War One Horses at war

Horses have been resident at the Fort both in the Victorian Era and during World War One and beyond.

Many of the horses for World War One were requisitioned from farms and owners across the land. A young boy talks about how he and the Colonel’s son watch the horses being exercised in the courtyard and the soldiers cleaning the tack. Next, a soldier describes how the horses were taken overseas to the frontline originally to be used in charged battle. Unfortunately the use of enemy machine guns made this a pointless tactic, which lead to high casualties. Instead the horses were used as pack animals to carry and draw equipment. Unfortunately this was still a very hard life for the horses with difficult conditions and high risk. We experience their hardships over the sounds of gunfire and explosions.

Many of the horses for World War One were requisitioned from farms and owners across the land. A young boy talks about how he and the Colonel’s son watch the horses being exercised in the courtyard and the soldiers cleaning the tack. Next, a soldier describes how the horses were taken overseas to the frontline originally to be used in charged battle. Unfortunately the use of enemy machine guns made this a pointless tactic, which lead to high casualties. Instead the horses were used as pack animals to carry and draw equipment. Unfortunately this was still a very hard life for the horses with difficult conditions and high risk. We experience their hardships over the sounds of gunfire and explosions.

A poem from the point of view of the horse owners is read out:

We didn’t know much about it

We thought they’d all come back

But off they all were taken

White and brown and black;

Cart and cab and carriage,

Wagon and break and dray,

Went out at the call of duty.

And we watched them go away.

All of their grieving owners

Led them along the lane

Down the hill to the station.

And saw them off by train

They must be back by Christmas,

And won’t we give them a feed.

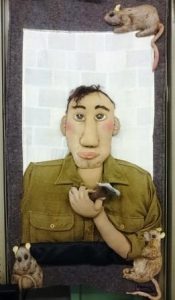

ABLUTIONS ROOM – World War Two A close shave

Every soldier was expected to use these facilities everyday to keep himself and his uniform presentable for the daily inspections.

A soldier describes his experiences in the room- “Imagine getting up on a cold morning and washing in this ablutions room in cold water because the boilers were very rarely lit! All the basins would be occupied by a cold and miserable man and it was a case of pushing each other out of the way and grabbing a basin. We were often washing in cold water so you wanted to be in and out as quick as you could. The soap we used was none of the fancy soap we get today- it was one of the general issue soaps- a kind of block of carbolic disinfectant type or if you wanted to you could buy yourself a scented one from the NAAFI. Shaving in the ablutions room was a hurried process. Someone gave me a razor and shaving brush and said you shave tomorrow – I said I didn’t need to – they said I did, so thereafter I had to shave! That shaving brush and razor were part of my issued equipment, which I signed for and was responsible for. If either wore out you went to the stores and paid for a replacement.

A soldier describes his experiences in the room- “Imagine getting up on a cold morning and washing in this ablutions room in cold water because the boilers were very rarely lit! All the basins would be occupied by a cold and miserable man and it was a case of pushing each other out of the way and grabbing a basin. We were often washing in cold water so you wanted to be in and out as quick as you could. The soap we used was none of the fancy soap we get today- it was one of the general issue soaps- a kind of block of carbolic disinfectant type or if you wanted to you could buy yourself a scented one from the NAAFI. Shaving in the ablutions room was a hurried process. Someone gave me a razor and shaving brush and said you shave tomorrow – I said I didn’t need to – they said I did, so thereafter I had to shave! That shaving brush and razor were part of my issued equipment, which I signed for and was responsible for. If either wore out you went to the stores and paid for a replacement.

Everybody’s razor and shaving brush was the same, so to make sure they didn’t go missing, you stamped the identity number on the side of them. Invariably one of the points on the daily inspection would be to check you had shaved and God help you if you hadn’t! Some people who had heavy growth needed hot water to get a proper shave. They would take their mug over to the cook house to get a cup of hot water, but it has been known if no water was available- they might bring back a cup of tea from the cook house and occasionally shave in that! To the right you can see the big blanko table, we had a set of webbing equipment which had to be scrubbed, then blankoed, then dried then squared off and everyone had to blanko the belts and the kit. If there was a big inspection coming up they would have a problem getting in to the blanko table to clean your kit and that blanko table must have seen many a petty squabble in its day! Conversely at other times when everyone was in a good mood and getting ready to go out for the weekend, you would get two or three people blankoing away and singing away quite happily together.

There were rats around the fort and they did get a bit cheeky and sometimes they would come out in the ablutions and watch you doing your business! Once, there were about four or five of us having a good natter getting ready to go about, when suddenly I spotted out the corner of my eye, sitting down looking at us- was a big rat. As I spotted it, one of the other lads spotted it and that alerted the rat who panicked and ran around the ablutions room twice. It disappeared through the back room amid the chaotic sounds of a group of soldiers chasing it!”

NAAFI – World War Two The Wedding

Fort Brockhurst was used during the Second World War for many different units. The original NAAFI was in the large building in the centre of the courtyard. The room you are in now was also used for leisure activities. Over the sound of soldiers eating, drinking and playing cards, we here an account of life in the NAAFI “NAAFI stands for Naval, Army and Air Force Institute, which are universal throughout the armed services in providing cafes, restaurants and recreational facilities. In the NAAFI you could buy extra supplies and food. If you were flush you could buy a cup of tea and a butted bun for sixpence. There were entertainment facilities in the NAAFI such as snooker tables and dartboards. “ An extract is read from a personal letter of a soldiers experience in the NAAFI “It was a lovely warm April day in 1943 and as I recall, we none of us, enjoyed the long march to Fort Brockhurst. I, for one, being only too pleased to hear the Sergeant Major bringing us to a halt on the square opposite a building we were soon to learn was the NAAFI. I spotted female faces staring at us from the upstairs windows; they hardly seemed impressed at the sight of three hundred weary chunkies. We were allocated our barrack rooms by sections and after the usual rigmarole of drawing palliasses and stuffing them with straw, securing our kit and partaking of a rather frugal cold meal, my pal and I decided to visit the NAAFI in search of a little extra sustenance.

Fort Brockhurst was used during the Second World War for many different units. The original NAAFI was in the large building in the centre of the courtyard. The room you are in now was also used for leisure activities. Over the sound of soldiers eating, drinking and playing cards, we here an account of life in the NAAFI “NAAFI stands for Naval, Army and Air Force Institute, which are universal throughout the armed services in providing cafes, restaurants and recreational facilities. In the NAAFI you could buy extra supplies and food. If you were flush you could buy a cup of tea and a butted bun for sixpence. There were entertainment facilities in the NAAFI such as snooker tables and dartboards. “ An extract is read from a personal letter of a soldiers experience in the NAAFI “It was a lovely warm April day in 1943 and as I recall, we none of us, enjoyed the long march to Fort Brockhurst. I, for one, being only too pleased to hear the Sergeant Major bringing us to a halt on the square opposite a building we were soon to learn was the NAAFI. I spotted female faces staring at us from the upstairs windows; they hardly seemed impressed at the sight of three hundred weary chunkies. We were allocated our barrack rooms by sections and after the usual rigmarole of drawing palliasses and stuffing them with straw, securing our kit and partaking of a rather frugal cold meal, my pal and I decided to visit the NAAFI in search of a little extra sustenance.

We entered the building and saw a small stage at one end with a moth eaten snooker table to its left: at the opposite end was a large rectangular serving hatch, whilst in between were a few dozen chairs and tables. Behind the counter were two girls wearing the familiar blue NAAFI overalls and they were deep in conversation with a couple of Royal Engineer Sappers. One of the girls was a very attractive little brunette and I immediately thought ‘Cor she’s nice, if she plays her cards right I’ll take her out’. My enthusiasm was not reciprocated however; in fact all four seemed totally unaware of our existence. We waited three or four minutes until finally, in desperation, and in a tone to fit the occasion, I pointed to the NAAFI sign above the showstand and asked brunette the meaning of the inscription SERVITOR SERVIENTIUM: ‘Ah’ she answered ‘That means serving those who serve’. ‘Oh yes’ I said and pointing to my battledress I asked ‘and what do you think this is, a pinstripe civvy suit?’ That did it, throwing her head aloft in righteous indignation, she turned to her helpmate and announced in a voice loud enough to be heard in the keep ‘You serve him Freda, because I’ll never serve that sarcastic pig, even if he’s here for the rest of his life!’ after which pronouncement she flounced out of the canteen and disappeared into the dark recesses of the kitchen. The proverbial dropped pin could have been heard as the two sappers glared at us and we glared back even harder. Seven weeks later Camilla still refused to serve me – seven months later on Christmas eve 1943, we were married. The whole of my platoon attended- even Fort Brockhurst’s Rat-catching dog was there! So you see Fort Brockhurst has a lot to answer for and I wouldn’t have had it otherwise.” We have depicted the scene of this marriage with the sound of a church organ being played.

For a large print downloadable/printable copy of the descriptive text click here